Yesterday a report I wrote for the European United Left/Nordic Green Left (GUE/NGL) group in the European Parliament was published. It was used as input for a hearing of the Parliament’s TAX3 committee, at which Hannah Tranberg from ActionAid, Eric Mensah from the Ghana Revenue Authority and UN Tax Committee, and Sandra Gallina of DG Trade spoke. (This link is to a video of the hearing, which begins with Margaret Hodge and Tove Ryding discussing Brexit, then moves on to the tax treaties discussion at around 16:30).

When the GUE/NGL approached me about working with them on this report, I jumped at the chance. It uses the Tax Treaties Dataset, a project funded by ActionAid and launched in 2016. Earlier this year I had used much of the same analysis in a European Commission workshop for treaty negotiators, and the comparative element certainly caught some of their attention. Just last week I used the dataset at a workshop of African treaty negotiators organised by the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie, at which it helped them to begin the process of analysing their treaty networks and developing renegotiation strategies.

But the EU is partiuclarly important. Most of the world’s tax treaties – and 40% of those with developing countries – have an EU member as signatory. Combined with its commitment to policy coherence for development, this makes the EU uniquely placed to ‘lead by example’. Indeed, the European Parliament has already called for “Member States to properly ensure the fair treatment of developing countries when negotiating tax treaties, taking into account their particular situation and ensuring a fair distribution of taxation rights between source and residence.”

The report has two main messages, from my perspective. The first is that, while the recent attention paid to treaty shopping is most welcome, the basic balance between ‘source’ taxing rights – which allow countries to tax inward investment from the treaty partner – and ‘residence’ taxation in tax treaties with developing countries is also a problem.

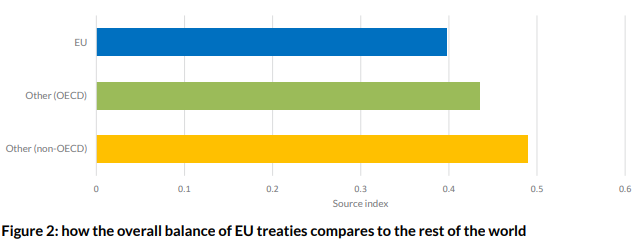

The dataset, which includes over 500 tax treaties signed by developing countries, includes a measure how much of a developing country’s source taxing rights each treaty leaves intact. It turns out that EU treaties remove more source taxing rights than average, even when compared with other OECD members.

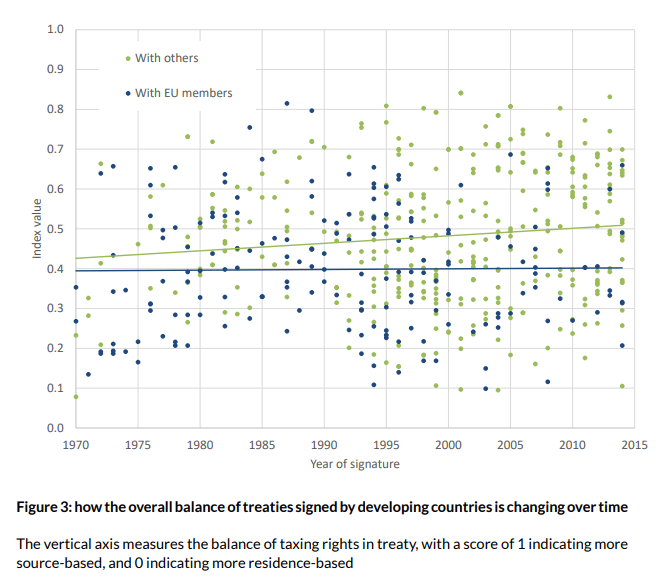

What’s more, the difference is growing.

Source/residence has been the elephant in the room in the debate over international tax rules in recent years, as we saw when it was dropped from the BEPS process at an early stage, only to re-emerge in the context of digital taxation. Countries conducting ‘spillover analysis’ or otherwise analysing their treaty networks need to take this into account.

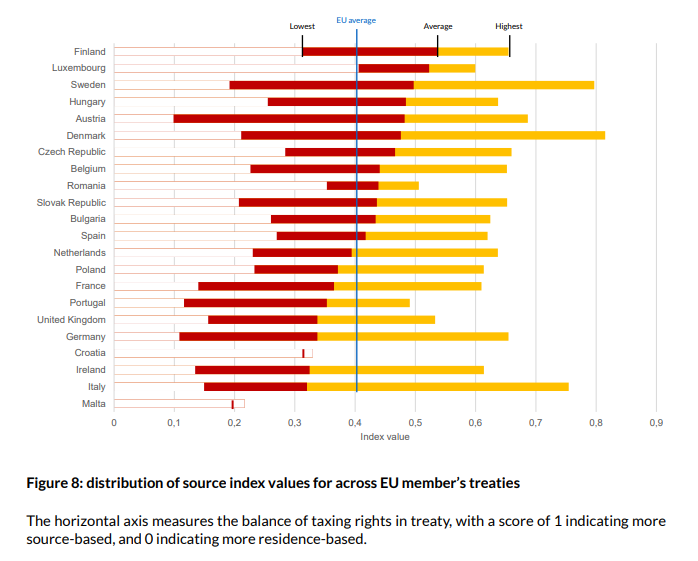

The second message is that there’s a great deal of variety within and between countries’ treaty networks. There’s loads of variation within each EU Member’s treaties, and between the average values for EU members. The same is true when drilling down to individual provisions. So there is plenty of potential to ‘level up’ based on precedent

The report echoes the European Parliament in arguing that, if the EU wants to be a leader on policy coherence for development, Member States need to level up the source taxing rights across the different provisions of their treaties with developing countries. Simply saying that on balance their treaties are no worse than anyone else’s – a point the report questions when looking at the EU as a whole – is not enough. The four summary recommendations are for Member States to:

- Conduct spillover analyses incorporating reviews of their double taxation treaties, based on the principle of policy coherence for development and taking into account guidance from the European Commission and other bodies.

- Undertake a rolling plan of renegotiations with a focus on progressively increasing the source taxation rights permitted by EU members’ treaties.

- Reconsider their opposition to a stronger UN tax committee, as the Parliament has previously requested.

- Formulate and publish an EU Model Tax Convention for Development Policy Coherence, setting out source-based provisions that EU member states are willing to offer to developing countries as a starting point for negotiations, not in return for sacrifices on their part.

Hi Martin, All in good. But it won’t help much as long as EU countries maintain their strict limitations on foreign tax credits. Regards, Hans